Interview with Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann

Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann

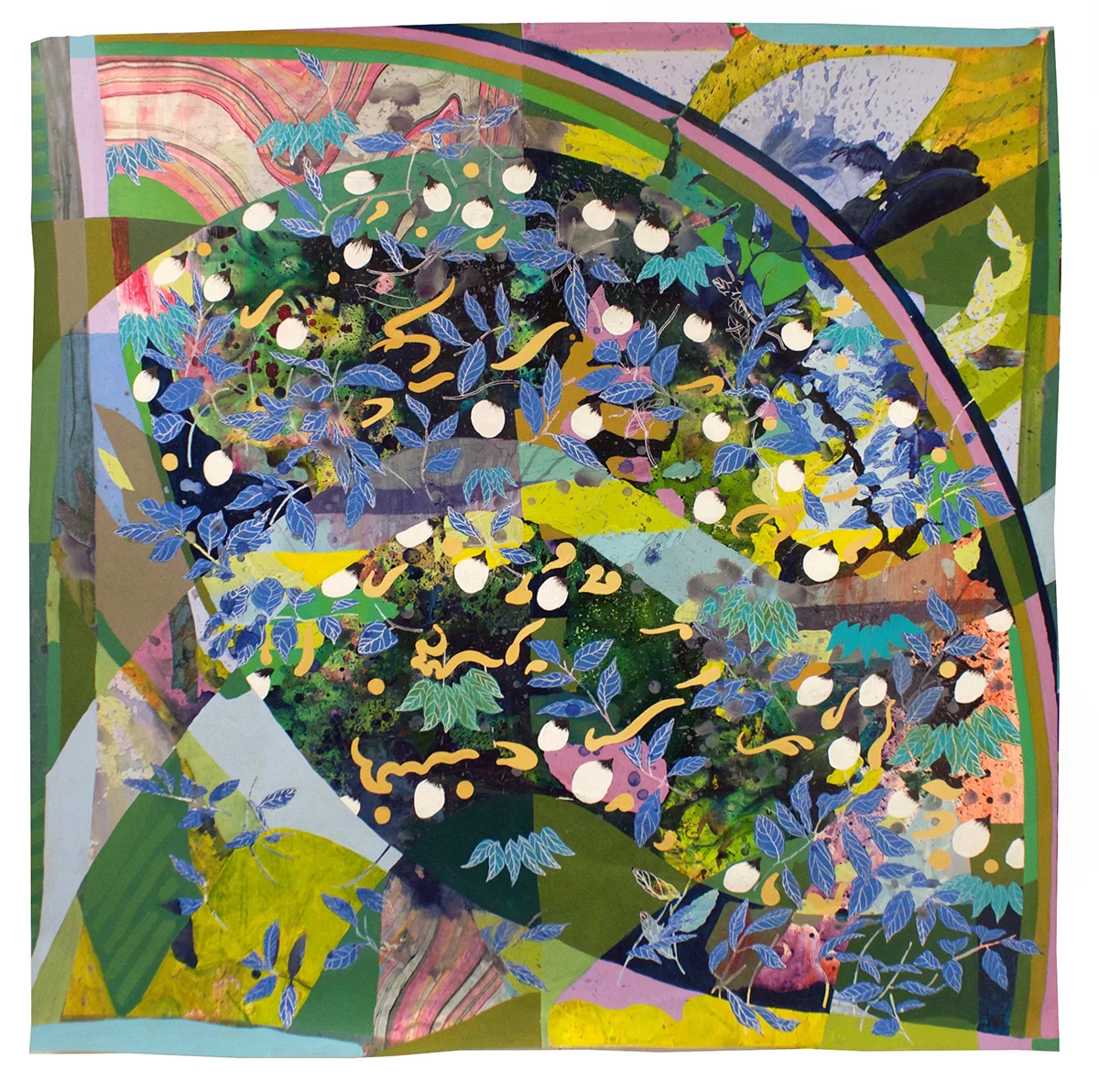

Dunhuang 5, 2016

Acrylic and sumi ink on collaged woven paper

detail

Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann is a Washington DC area painter who received her BA from Brown University and MFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art. In this interview she speaks to Ty Bishop, Publisher of Friend of The Artist, about her studio practice, recent installation at the Facebook Washington DC, and gives advice to emerging artists.

TB: How did you get started painting?

KTM: I have painted all of my life, but I was originally trained, as a teenager, as a traditional sumi ink painter. I’m half Taiwanese, and lived in Taiwan as a child—there I would copy my teacher’s bamboo, landscape, and flower paintings.

TB: Is there any correlation between when you started and your current practice?

KTM: My work no longer fits neatly into a purely traditional Chinese landscape history. But this background is the skeleton of my work now: an interest in the materiality of water, ink and paper; landscape and depth through layers and incongruity rather than perspective; romance and utopia created through immersing a viewer in detail.

One of my favorite parts about your work is that there is so much to look at. It’s impossible to take in at once. Tell me about the what goes into each painting as far your reference imagery and process.

I have a lexicon of images and symbols that often go into paintings, and that I’ll often repeat. I think of all of my work as landscape oriented, or painting that has to do with our environment and ideas of landscape. So I use a lot of natural and botanical imagery—plein air painting of leaves and brush, as well as highly symbolic floral imagery with deep cultural reaches into Chinese art history (peonies, chrysanthemums, peaches) or European art history (tulips). I’ve been looking at a lot of ancient wall painting, from Buddhist cave paintings in Dunhuang, China, to garden frescoes in Rome. In both of those examples, you can see painting as a type of magical tool: in tombs it transports the dead to another realm while the act of painting is in itself transportive and devotional, in homes it becomes a road map to escapism and utopia.

I also use a lot of stereotypically feminine or decorative imagery, such as braids of hair, ribbons and bows, flowers and baubles. All of these familiarly pretty symbols and rebuses take on a new life when repeated and placed into my alien and abstract environments: they become biomorphic, overgrown, even cancerous, but also, I like to think, fabulous.

Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann

Breaker, 2018

Acrylic, latex paint and collage on walls and stairs at Facebook Washington DC

5 x 30 x 30 ft.

TB: What is the significance in the materials you use?

KTM: I start all of my paintings with a pour: the paper lies on the floor of the studio and I pour diluted ink or paint onto it. Eventually, the water dries, leaving pigment in an alluvial deposit, or stain. This is the spine around which I build the rest of the painting, combining hard edged pattern, delicate drawing, and hamhanded swathes of color… but that stain exists because of the materials of ink and paper. Sometimes I will collage, cut or weave the paper, sometimes I’ll collaborate on, squeegee out, or obliterate the stain, but that first painting move and all others are at heart an ode to paper and water.

TB: You recently completed an installation for the Facebook office in Washington, DC. How did this opportunity come about and what were some challenges you faced with the space?

KTM: I was lucky enough to create a mural that bled from a wall onto a set of stairs in the middle of the Facebook Washington, DC office space. I have to thank Tamara Weg, the curator of that program, for forcing me out of my comfort zone and making me think of painting on the stairs in the first place. I had to deal with painting on concrete on a surface that would be walked on, but it also afforded me a chance to make a multilevel, truly immersive space: I always like my work to feel like it could bleed into and annex a space, and this piece made that sense literal.

Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann

Bow, 2017

Acrylic and sumi ink on paper

52 x 53 in.

TB: What advice would you give to artists just starting their careers?

KTM: Focus on making good work in as close as you can create to a studio setting, even if there are no opportunities for showing that work, then get used to applying to grants, juried shows, and residencies as your second job in order to get that work out there. And then get used to being rejected from the things you apply to, but continue making the work anyway. Amidst those rejections will be some acceptances. Repeat, and build your career, colleagues, and collaborations from there. Collaboration is full of wonder. Don’t relegate your art making to stolen moments. Having a family is totally possible.

TB: What is the best part about being an artist?

KTM: I became an artist because painting is the best way I could imagine spending my day. But it also has the benefit of training your mind to question and exist at least a little apart from the (capitalist, patriarchal, colonialist, etc) systems that surround us in our American society. It’s a gift that makes the world, and the people who view it, weirder—and as an artist you get to spend your whole day straining to imagine ways to break your own ossified shortcuts and assumptions. (I also think parenting does this.) What could be better?