Interview with Bhimanshu Pandel

Bhimanshu Pandel

Bhimanshu Pandel (b. 1995) is a visual artist and researcher based in Rajasthan, India, whose practice explores ecological and cultural elements in the desert landscapes of the region. Rooted in his family’s agrarian heritage, his work engages with native plants, regional myths, cultural tools, and natural minerals to explore the living histories of indigenous communities. He works across drawings, sculptures, and site-specific installations.

INTERVIEW WITH BHIMANSHU PANDEL BY LAURA DAY WEBB

How did you embark upon a career as an artist and what resonated with you about this path?

I don’t think I set out to be an artist in the professional sense of the word. Having grown up seeing my grandfather’s documentation of rural Rajasthan as a social worker, which was an extensive archive of photographs he had made for over 3 decades in the 1962- 1995, shaped how I perceived the world and culture around me. I was inspired and drawn towards the region’s oral history, how cultural objects carry narratives of agrarian communities and traces of post-colonial shifts. Over time, this developed into a practice where I attempt to understand and reinterpret these very elements that constitute the socio-cultural fabric of desert communities in Rajasthan. After studying in Edinburgh and Switzerland, I returned to India to confront two fundamental questions: who I am and where I come from. This sense of ambiguity largely informed my artistic practice as tied to the immediate culture I come from.

I often approach work through a framework of personal field research spanning different villages across the Marwar region, engaging with people of agrarian communities and mapping out a kind of archive which includes orally transmitted stories, genealogical records, collecting objects (bullock carts, earthen pots, miscellaneous household items, farming tools, ornaments, textiles etc.). This exercise serves as the structural groundwork for my drawings, sculptures, installations, and prints.

Your work draws inspiration from your heritage. Can you share more about how it informs your practice?

Primarily, I was interested in heritage which is more aligned with oral traditions as opposed to the royal/classical heritage which has dominated mainstream historical narratives in Rajasthan. Unlike documented history, folk heritage lives in speech, memory, and practice, shaping the daily lives of agrarian communities rather than being confined to glorious artefacts.

This evolved into an inquiry within my own agrarian community, where survival is shaped by the struggle against arid desert landscapes. Despite its dryness, this space holds deep cultural significance—14th-century oral epics are still recited, revealing insights into the region’s history and present day concerns. Land, water, and farming are not just livelihoods but integral to the cultural fabric, carrying indigenous knowledge systems that persist in small numbers. My work engages with these systems, and what intrigues me has been the visual and material expressions which have been preserved through oral traditions—but which now face the risk of being effaced as indigenous communities continue to grapple with post-colonial shifts.

The diverse nature of your work spans an array of mediums and sizes. How do the various facets of your practice inform one another? Do you often work across multiple mediums simultaneously?

I enjoy the exploration of mediums, seeing how the same thematic engagement with ecology and ecological practices of desert communities can be explored through various materials - in the form of drawings, sculptures, and site-specific installations. All of them share a common idea of reference. I collect various native shrubs, cacti, tools, natural minerals etc. and study their form and structure as the basis for my drawings and sculptures. Exchanges with local indigenous communities such as the Bishnoi, Rebari, Banjara, and Meghwal etc. have also been important for me to understand ideas of collective memory, regional myths, the sacred significance of particular plants etc., which constitute the underlying vein of my practice.

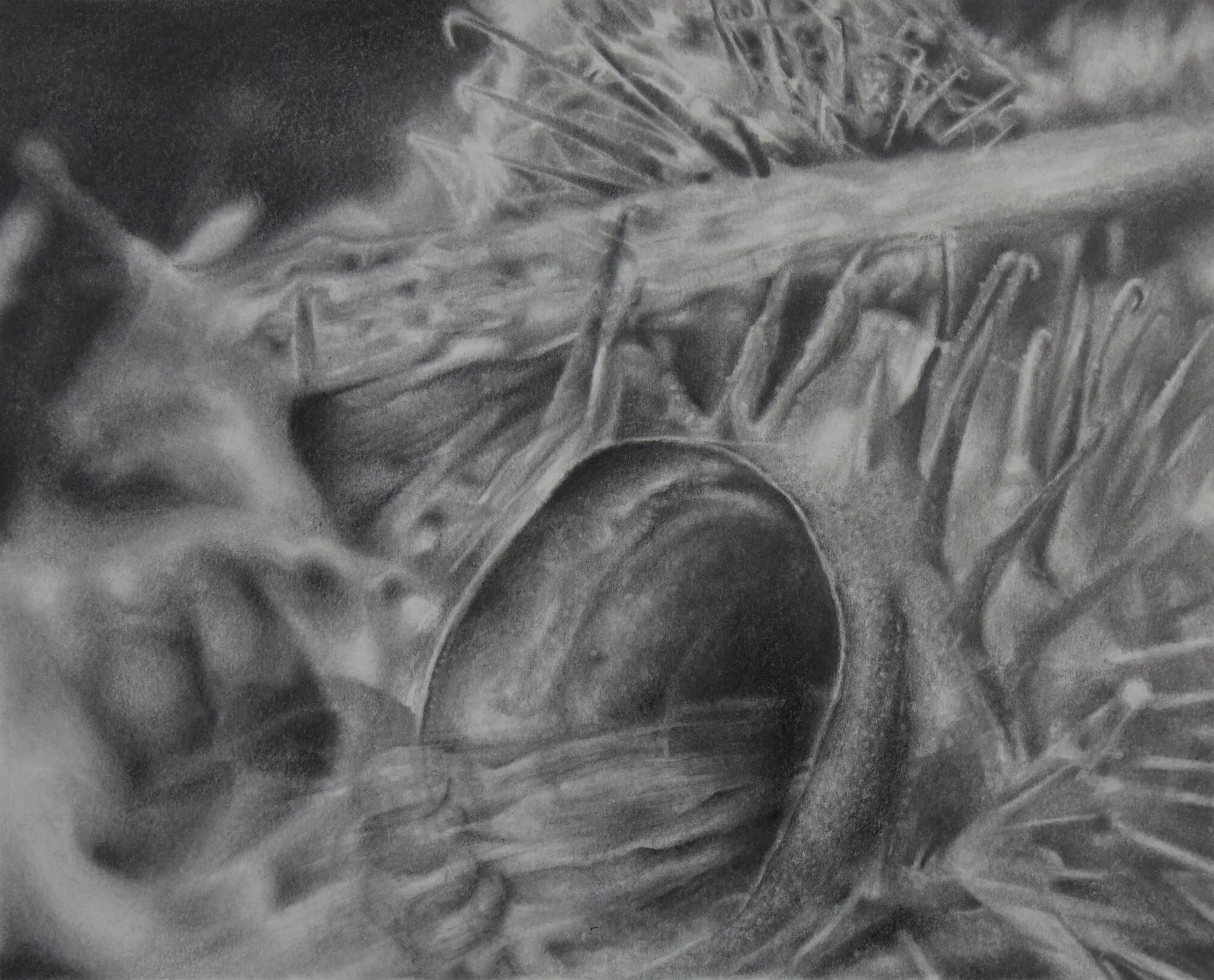

The materials I use are determined by the visual or emotional landscape needed to bring out the imagined form. In Whispers of the Village Punlota, I explored the death of bui (a regional weed) due to an invasive force, symbolizing ecological disruptions, using materials like wood, lime, hay, jute etc to create the humanoid forms. In the installation piece Ghar Aangan: Guad Main Kheta Ri hi Goonj, I sought to portray the cultural significance of opium through an assortment of various materials like wood, metal, glass, ceramic (raku), mud sourced from desert land etc. The idea was to merge the domestic and the agrarian, to depict the echo of the fields within the setting of a house, and informed by the same element of the invasive force brought about by colonialism. In my drawings, I generally work with graphite, but I continue to experiment with different mark-making techniques using non-conventional tools to achieve an ephemeral line, as if viewed through glass, on various types of paper. Recently, I have also been experimenting with indigo powder.

Is there a particular series or exhibition you are working on that you would like to share with readers?

I have several ongoing experiments/projects that I’ve been developing for a while. One is perfecting a culturally significant and traditional dry stone wall and lime technique, adopting its forms and materiality. Another project is the construction of a water reservoir, designed to store natural water year-round—I imagine this as a land-based work which will remain intrinsically connected to the ecological and agrarian needs of the region. I have also been working on documenting cultural objects dating as far back as the 17th century, such as household utilitarian objects and tools, ornaments, textiles, ritualistic artefacts etc. to create an archive that reflects the passage of time as seen through the evolution of their forms and functions.

The studio can be a place of sanctuary and inspiration. Are their particular rituals, music, or other elements that you incorporate when beginning a new piece?

I generally like to begin a new piece of work in the morning when the setting of my studio feels the most ideal. Taking a walk helps me visualize things a lot more clearly. This is when I sort of visualize the forms I plan to draw or sculpt. Sometimes I like to first read short stories and pieces that I often revisit every now and then before I sit on a piece. The language of writers like Márquez, Juan Rulfo, Vijaydan Detha, and Lévi-Strauss have been very formative to me. Other times I play some tunes, mostly ones with a clean and clear rhythm, or listen to recordings I’ve made over the years in my visits around Rajasthan. It’s about creating a familiar yet charged atmosphere that is rooted in routine.

Finally, if you could study with an artist past or present, who would it be and why?

Adrián Villar Rojas and Thomas Houseago. I have been exploring a lot of Latin writings, and Villar Rojas' work - the sheer monumental scale of it and the refinement with which he wrings his forms into life, like the one in Venice, creates an almost palpable resonance with the spirit of Latin literature. Similarly, Houseago’s approach to materials and his sculptural, non-academic way of seeing sculpture—as an assemblage made of 2D elements and drawing panels—gives it a formidable weight in spite of its actual lightweight physical quality. The work of these two artists drives home an understanding of how a myth becomes alive for me.

FEATURED WORK